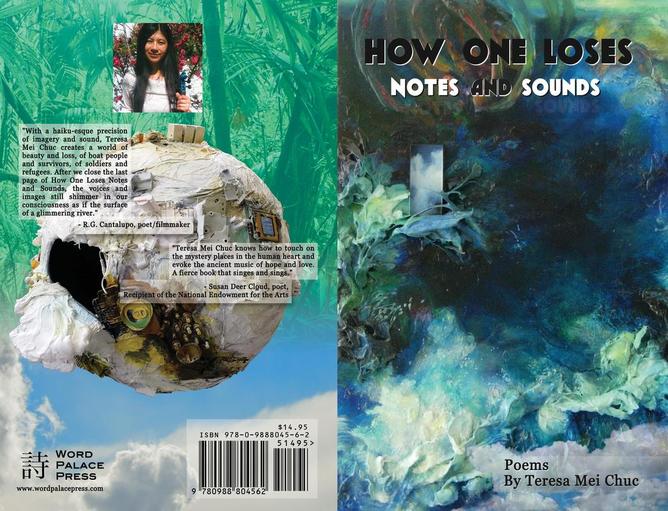

Front cover painting, "Box of Water" by Ann Phong

Back cover painting/art, "Human Traces on Earth" by Ann Phong

Chapbook release date: February 17, 2016

To purchase a copy of How One Loses Notes and Sounds by Teresa Mei Chuc, please go to Word Palace Press. http://wordpalacepress.com/

How One Loses Notes and Sounds is also available on Amazon.com

"Teresa Mei Chuc's new poems are as heartbreaking as they are exhilarating and inspiring! With a haiku-esque precision of imagery and sound, she creates a world of beauty and loss, of boat people and survivors, of soldiers and refugees. After we close the last page of How One Loses Notes and Sounds, the voices and images still shimmer in our consciousness as if the surface of a glimmering river." --R. G. Cantalupo, poet/filmmaker

"Teresa Mei Chuc’s How One Loses Notes and Sounds is a book of bearing witness to immense tragedy while also recovering life’s lost “notes and sounds” via the alchemy of poetry. This writer, once a child refugee from Saigon at the end of the Vietnam War, possesses the gift of our greatest poets inasmuch as she weaves together many strands of often ravaging experience into a starburst of transforming light. Her poems are a marvel in the way they attend to that which is cruel, pitiless and murderous in our world yet infuse such ugliness with poignant beauty and compassion. Teresa Mei Chuc knows how to touch on the mystery places in the human heart and evoke the ancient music of hope and love. A fierce book that singes and sings."

--Susan Deer Cloud, poet & NEA Fellowship recipient

Back cover painting/art, "Human Traces on Earth" by Ann Phong

Chapbook release date: February 17, 2016

To purchase a copy of How One Loses Notes and Sounds by Teresa Mei Chuc, please go to Word Palace Press. http://wordpalacepress.com/

How One Loses Notes and Sounds is also available on Amazon.com

"Teresa Mei Chuc's new poems are as heartbreaking as they are exhilarating and inspiring! With a haiku-esque precision of imagery and sound, she creates a world of beauty and loss, of boat people and survivors, of soldiers and refugees. After we close the last page of How One Loses Notes and Sounds, the voices and images still shimmer in our consciousness as if the surface of a glimmering river." --R. G. Cantalupo, poet/filmmaker

"Teresa Mei Chuc’s How One Loses Notes and Sounds is a book of bearing witness to immense tragedy while also recovering life’s lost “notes and sounds” via the alchemy of poetry. This writer, once a child refugee from Saigon at the end of the Vietnam War, possesses the gift of our greatest poets inasmuch as she weaves together many strands of often ravaging experience into a starburst of transforming light. Her poems are a marvel in the way they attend to that which is cruel, pitiless and murderous in our world yet infuse such ugliness with poignant beauty and compassion. Teresa Mei Chuc knows how to touch on the mystery places in the human heart and evoke the ancient music of hope and love. A fierce book that singes and sings."

--Susan Deer Cloud, poet & NEA Fellowship recipient

April 12, 2016

On Poetry and How One Loses Notes and Sounds

by Teresa Mei Chuc

I was born in Saigon, Vietnam and immigrated to the U.S. with my mother and brother shortly after the Vietnam War while my father remained in a Vietcong reeducation camp for nine years. I was about 2 ½ years old when I arrived in California. English was my third language. Vietnamese and Cantonese were my first two languages. At home, I was only allowed to speak in Vietnamese or Cantonese. At school, I initially struggled with speaking English and with expressing myself in English. I walked in between cultures, lands and languages in a space that was not really here or there, each step trying to return home but not really sure where that home was or where it began. When I discovered poetry, I discovered a vehicle of expression that transcended language, a space that allowed me to be free and at home, a space that allowed me to be myself in the embrace of all of my cultures, lands and languages, a space that allowed my emotions and mind to grow and be expressed. I was not tied to grammar or spelling or rules; I was able to create and recreate myself in a world that constantly strived to mold me, to assimilate me, to defeat me. Through poetry and its empowerment, I was able to return to myself and eventually to my first language - the language of the heart that was beyond any language.

Rainer Maria Rilke had the greatest impact on me as a poet. He encouraged me to trust myself, to be patient, to let my words gestate. He taught me about the growing and gestation of life, of birth, of death. He taught me that in my solitude, in the deepest, darkest corners of myself, I will stretch myself and open myself further. He taught me not to be afraid of dragons and to face them. Letters to a Young Poet and Duino Elegies are some of the works by Rilke that had the most profound influence on me as a poet and person.

My poetry deals a lot with war, the Vietnam war, other wars, the immigrant experience, the consequences of war and bearing witness and in doing so opening our minds to our shared humanity. I think in my newest book, How One Loses Notes and Sounds, I experimented with more forms than in my previous books. My new book contains lyrical poems, narrative poems, haiku, senryu, haibun, a sonnet, a ghazal and a villanelle. The subject matters were about war, immigration, and the struggle of women and suicide. I found that as I wrote “Sonnet of the Syrian Refugee,” “Ghazal: Kindness,” “Operation Frequent Wind” (a haibun), and “Shame” (a villanelle), the forms allowed the subject matters to sing and gave the subject matters a vehicle of containment and expression...they held the energy of the pieces. The repetition of the villanelle, “Shame,” is haunting as images repeated, and I wanted the reader to feel this haunting as the girls in the poem felt and also a feeling of being trapped in this repetition of the villanelle as the girls in the poem felt trapped. I think the rhyme scheme in “Sonnet of the Syrian Boat Refugee” itself becomes a boat in the waves, rocking in its loneliness. The ghazal and the repetition of the word “kindness,” especially at the end of the line, creates a juxtaposition in the situation of the poem...kindness in a place of war and conflict. When you place two things that are in contrast next to each other, both are enhanced (black/white) and I wanted to make this apparent and unavoidable.

Writing "Operation Frequent Wind" in haibun allowed me to describe in detail the situation during the last days of Vietnam when the South Vietnamese were trying to flee the country and the haiku/senryu at the end of the poem allowed me to zoom in and connect the situation with nature in its simplicity, thus adding a new dimension to the poem and connecting our situation or story to a larger narrative in the natural universe. The earth also speaks our story.

My hope is that through poetry, we can connect with each other on a human and compassionate level. Oftentimes, when we read the news or history books, people and events become statistics or the narratives are told by the victors or the ones in power. I wanted to give voice to those stories which must pull themselves up from a silent, dark well into the light so that we may be aware of the consequences of war and the courage and strength and love of human kindness...So that we may continue to survive in our humanity as in the narrative of the Vietnamese boat people in my poems, “Quan Âm on a Dragon” and “Family."